Supply chains, inflation and the currency market.

November 2021

It’s hard to believe after the year we’ve all been through, but Christmas is just around the corner. And while consumers will be eagerly awaiting the end of year break, many businesses are sweating.

It’s all to do with the supply chain. After nearly two years of shutdowns and lockdowns, getting the global machinery of production to function smoothly is taking time.

We live in a world built on the premise of ‘just-in-time’ production – a process whereby the minimum amount of necessary parts needed to produce a product are ordered. Such a process saves on shipping and handling, storage costs and working capital. It requires a robust analysis of likely consumer demand and resulting inventory needs and rock-solid confidence in logistics.

When it all works well, it keeps costs down and profits up at the firm level and helps keep prices down for consumers. When it doesn’t work, such as, say, the end of a pandemic, prices can spike.

For currency markets, the impact of supply bottlenecks on rising prices is starting to weigh more heavily. Central banks have been holding back on raising interest rates from record lows on the assumption that the high rates of inflation caused by supply-related price spikes are only transitory. The overarching narrative has been that challenged supply amid a period of high post-pandemic consumer demand will be short lived and that once factories get back to full production and logistics issues are ironed out, inflation will return to normal.

But not everyone agrees this is a short term blip.

A Wall Street Journal survey of 67 business, academic and financial forecasters conducted in October found that inflation projections are up dramatically from July with economists on average expecting inflation of 5.25% in December. If it holds at a similar level in October and November, that would mark the longest period that inflation has been above 5% since early 1991.

Of the economists surveyed by the Wall Street Journal, half cited supply-chain bottlenecks as the biggest threat to growth, with 45% saying they don’t expect the issue to be resolved until midway through next year.1

The problem is two-fold. On the one hand demand is skyrocketing. Many governments are still in stimulus mode in an attempt to get their economies back on track. Cash is flowing into citizens’ pockets, as well as towards big infrastructure projects. As economies reopen, shoppers are returning to stores and diners to restaurants, so stock needs to be available. At the same time, ecommerce has been through a step change and consumers are purchasing online like never before, including cohorts – like the elderly – who were forced to make the switch and found they liked it. This is taking place all over the world, in a near coordinated fashion, so the effect is amplified.

On the other hand, the global machinery to meet all this demand has had to ramp up from the stop-go production challenges caused by COVID-19. Factories in major areas of production, like textiles in India, microchips in Taiwan and apparel in Asia had to close as workers were sent home. While most are back up and running, the backlog in orders caused by the surge in online shopping during the pandemic still needs to be satisfied.

But it’s not just the product itself that is the problem, the logistics infrastructure that is finely tuned to the just-in-time nature of global trade has also been affected.

With Black Friday and Christmas around the corner, many companies are stocking up to greater degrees than usual – they don’t want to be caught short during the anticipated period of high demand.

What that means is that as retailers and others order extra goods, they need extra space to keep it. Warehouse space is at a premium, meaning many are opting to leave their goods for longer at ports in shipping containers, or holding on to those shipping containers for longer and not returning them back to the system. Nearly 13 percent of the world’s cargo shipping capacity is tied up by delays, according to logistics experts.2 The system is so clogged that largest port in the US, Los Angeles/Long Beach, had a record number of ships waiting to offload in October.

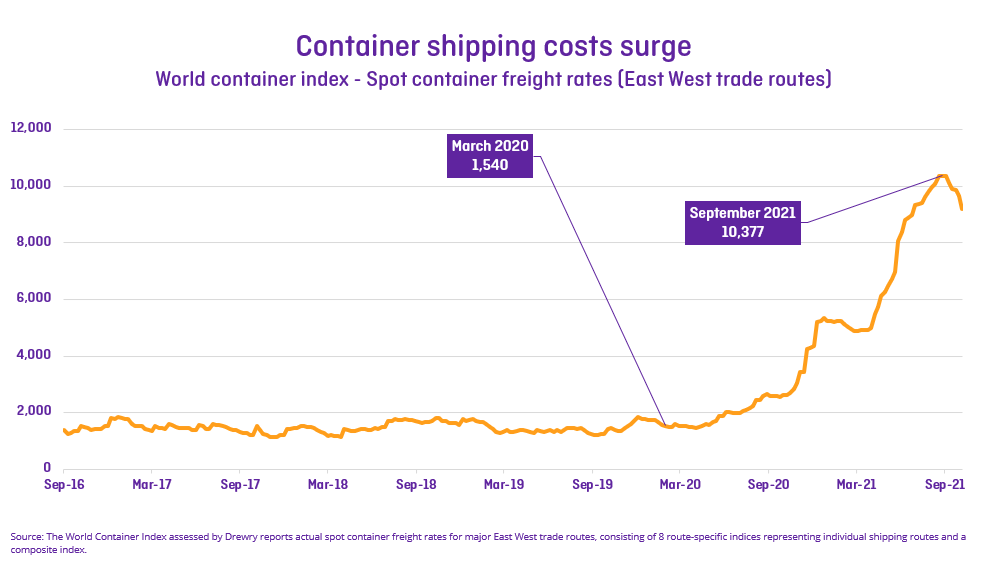

In Australia, for instance the competition regulator has discovered that some of the nation’s largest retailers have become so desperate for shipping containers that remain in short supply that they have resorted to buying their own containers and chartering their own vessels to transport cargo.3 It’s a costly solution — chartering extra ships to clear the backlog is five times as expensive as a year ago and the price of a 40-foot container has almost doubled as well.4

It’s not just the containers themselves that is the issue, one major Australian retailer has described the global shortage of pallets (used to store stock on in a fork-lift friendly way) ‘palletgate’.5 Not only is a shortage of wood to make the pallets one issue, another is the fact that pallets aren’t being returned to the system as quickly, as stock sits for longer on pallets in warehouses.

Globally, companies are counting the costs and putting up prices. Appliance manufacturer Whirlpool said “inefficiencies across the supply chain” would add $US1 billion to costs this year as it struggled to get steel and resin. Procter & Gamble announced price rises for nine of its ten product categories in the US.6 A survey by Oxford Economics conducted in October found that manufacturing production costs are up an ‘eye-popping’ 40%-50% year on year, noting an extreme imbalance between raw materials and finished goods.

Many companies are worried about transferring these costs on and spooking customers who are only just emerging from a global recession. If they raise prices too soon and bottlenecks ease, they may lose market share to competitors who hold prices steady.

Central banks have a similar problem. They are trying to steer their economies out of the pandemic slowdown and they don’t want to choke growth by raising interest rates to prevent an outbreak of inflation. They are also in competition in a way, just as corporations are. One of the areas that helps economic growth is a lower currency relative to other countries — it makes exports more competitive.

If a central bank raises interest rates, its currency also rises as investors move their money there in pursuit of a higher return. It is a high-stakes game and those who move first are taking the bet that the pain of currency appreciation and potentially slower growth now is preferable to inflation getting out of hand.

References

1. https://www.wsj.com/articles/supply-chain-bottlenecks-elevated-inflation-to-last-well-into-next-year-survey-finds-11634479202

2. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/11/business/supply-chain-crisis-savannah-port.html

3. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/economics/port-delays-crippling-economy-accc/news-story/e2e67d7709f09243c9be037803f2abfd

4. https://www.afr.com/policy/economy/why-australia-is-running-low-on-timber-cars-and-pianos-20210519-p57tcp

5. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/retail/supermarkets-and-suppliers-form-taskforce-to-find-missing-wooden-pallets-that-could-hit-supply-chain/news-story/a0f4f5d5b1761f62047b074cccbafe31

6. https://www.ft.com/content/36f0b102-b9a0-4f52-96b3-fc3a51729375

Download the OFX Currency Outlook

Learn more in the latest edition of the OFX Currency Outlook. It’s been produced to help you navigate market movements today, and to understand what to watch out for in the coming months.