What a global meeting of central bankers is telling us about the economy

By the OFX team | 12 Sept 2023 | 9 minute read

Late last month, the great and the good of the global banking world was in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, giving us possibly the clearest roundup of how three years of economic turmoil has reverberated throughout the world.

Economic shocks aren’t new, of course. In the hundred years since the Great Depression, they have occurred at the rate of approximately one a decade.

But each time is different, and the policy responses from governments and central banks are often enacted with imperfect information.

As US Federal Reserve Chair, Jerome Powell told the attendees at the Jackson Hole Economic Symposium, “…we are navigating by the stars under cloudy skies1.”

That was certainly the case in the last 3 years when a global pandemic and the invasion of Ukraine saw interest rates in most developed countries slashed to zero (or near zero) and then rapidly ratcheted up in a bid to curb fast-growing inflation.

Central banks essentially have one lever to work with, interest rates, so they’re using this blunt tool in an attempt to counter the effects of government policy, corporate activity and consumer sentiment. Only with the benefit of hindsight, can we see how difficult those decisions were and perhaps get a glimpse of what’s to come.

Lagging indicators

A number of central bank leaders pointed out how inflationary events rippled throughout the economy, and were amplified by government policy.

“Thanks to the particular way in which retail energy bills are calculated in the UK, the direct impact on the CPI and on real household income has been both larger and more drawn out even than in the rest of Europe,” Mr Broadbent explained.

Bank of England Deputy Governor, Ben Broadbent2 cited the impact of escalating gas prices caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, when the wholesale price of natural gas rose to over ten times the price of gas in North America and the equivalent of nearly $600 for a barrel of oil.

However, the impact of this price rise was stronger for longer due to the way the UK regulates energy prices.

“Thanks to the particular way in which retail energy bills are calculated in the UK, the direct impact on the CPI and on real household income has been both larger and more drawn out even than in the rest of Europe,” he explained.

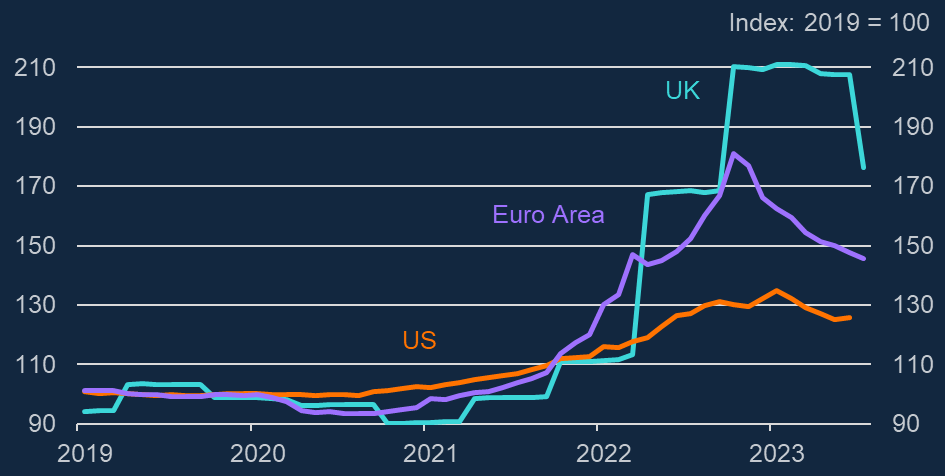

Utility bills rose further in the UK than in the rest of Europe and the US

As you can see from the chart, that drawn-out peak in UK energy prices kept the inflationary impact in place for longer, putting pressure on the Bank of England to continue to tighten rates.

Over in the US, Federal Reserve Chair, Jerome Powell highlighted the push-pull effect of government and central bank policy, colliding with the reality of constrained supply.

“The motor vehicle sector provides a good illustration,” Powell explained. “Earlier in the pandemic, demand for vehicles rose sharply, supported by low-interest rates, fiscal transfers, curtailed spending on in-person services, and shifts in preference away from using public transportation and from living in cities. But because of a shortage of semiconductors, vehicle supply actually fell. Vehicle prices spiked, and a large pool of pent-up demand emerged.”

That spike in prices fed straight into the inflation model, but now its effects are rapidly diminishing. The backlog of cars has now been filled but is being delivered at a time when interest rates on auto loans have nearly doubled since early last year, and customers are feeling the effect on affordability.

“On net, motor vehicle inflation has declined sharply because of the combined effects of these supply and demand factors,” Powell said.

In the US, a similar effect was felt in the housing market, again with a significant inflationary impact.

Rapid price rises crimped demand for new houses, and construction dropped off. But with not enough homes being built, rents spiked feeding the inflation model.

Like the UK and its sticky energy prices, due to the way bills are calculated, high rents take time to roll off. “Leases turn over slowly,” Powell pointed out. “It takes time for a decline in market rent growth to work its way into the overall inflation measure. Going forward… housing services inflation should decline toward its pre-pandemic level.”

The European Central Bank (ECB) sees another inflationary element3.

ECB President, Christine Lagarde partly laid the blame at the feet of corporations, saying the pandemic gave them cover to raise prices. In ordinary times, she suggested, competitive instincts would keep them raising prices for fear of losing market share.

“This changed during the pandemic as firms faced large, common shocks, which acted as an implicit coordination mechanism vis-à-vis their competitors. Under such conditions, we saw that firms are not only more likely to adjust prices but also to do so substantially,” Lagarde said.

“That is an important reason why, in some sectors, the frequency of price changes has almost doubled in the euro area in the last two years compared with the period before 2022.”

To summarise, central banks have been raising rates to combat inflation in the face of structural issues that keep prices higher than they would otherwise be.

Globalisation at an Inflection Point

Changing trade patterns was also a key talking point of the symposium, and the above heading is also the title of Bank of Japan (BoJ) Governor, Kazuo Ueda’s speech4.

Japan doesn’t have a problem with inflation, Mr Ueda said, but he is keeping a close eye on the impact of a changing geopolitical world where the US and China are battling for economic supremacy.

“It is very difficult at this point to detect the contribution of the geopolitical factors to the slowdown in the (Chinese) economy,” he said. “The tit-for-tat war, mainly in the semiconductor sector, between major advanced economies and China is a risk.”

What the BoJ is seeing already, however, is Japanese investment appetite shifting away from China and to the US and other nations in Asia. Japanese companies are moving from China and into Southeast Asian nations (collectively known as ASEAN), India, and North America. As Ueda explained, the move is “motivated not only by geopolitical considerations but also by demand increases in the host countries. Flows into the U.S. are also demand-driven but may be affected by U.S. industrial policies such as the IRA and the CHIPS and Science Act. as well. Friend-shoring and reshoring activities are taking place on a non-negligible scale”.

An International Monetary Fund paper, cited by Ueda, suggested that the world would see a significant decline in GDP if trade blocs between the US and China emerged. Asian nations, hitherto reliant on Chinese foreign investment would be particularly hard hit, the paper argued.

The BoJ is not seeing that play out so far, but a potential trade war will make the Bank’s job that much harder.

“Central banks will have a hard time factoring in these forces when making policy decisions. The economic outlook is clouded by a number of effects that geopolitics/de-globalisation could generate, (and) as production location shifts over time, researchers will find it difficult to obtain stable statistical results involving regional variables,” he said.

With a strong domestic production base, Japan is much better placed to ride out a trade war than the UK and Bank of England Deputy Governor Monetary Policy, Ben Broadbent demonstrated just how exposed the British economy is to de-globalisation.

Free trade was a boon in terms of reducing prices for many years, but leaving Brexit, the pandemic and the invasion of Ukraine sent prices in the opposite direction as imports cratered.

“The experience of an open economy like the UK provides a stark illustration of the cost of a sudden contraction in the supply of traded goods,” Broadbent explained. “Together with a tight labour market, the resulting squeeze on income is likely to have contributed to the sharp rise in domestic inflation and the consequent tightening of monetary policy.

“It’s unlikely these effects will unwind as rapidly as they emerged. As such, monetary policy may well have to remain in restrictive territory for some time yet.”

Massive government spending complicates the problem

The forces at play outside of central banks’ control don’t even take into account the enormous amount of investment required to deal with climate change and a more perilous security situation.

The ECB’s Lagarde referred to an energy transition that will require massive and rapid investment – around €600 billion on average per year in the European Union (EU) until 2030.

Global investment in digital transformation is expected to more than double by 2026, she said and the EU will be required to boost defence spending annually to meet the NATO military expenditure target of 2% of GDP.

All this spending – on green materials and semiconductors (for both domestic and military use) in the face of supply constraints will result in “stronger price pressures in markets like commodities.”

Wages are the ones to watch

Central bankers are telling us that the factors driving inflation are highly susceptible to issues outside their control.

But keeping inflation at a moderate rate — usually somewhere be 2% and 3% — is their primary focus. And the one big factor they are most focused on is wages.

A wage-price spiral, where increasing prices, leads to increasing wage demand, leading to increasing prices is the one outcome they are most desperate to avoid.

A UK resident wouldn’t be thinking of the fact that electricity prices get rebased once a year when asking for more money to cope with soaring power bills, however. An American worker wouldn’t notice that rents have gone down unless they move, and even then the effect of decreased affordability will linger.

When imports decline due to a trade war by as much as 30% as ECB research suggests, the cost of living goes up. Workers will expect to be compensated for that.

When governments reshore industries, as the US has with hi-tech manufacturing, wages for skilled workers rise, and other workers will be more inclined to advocate for higher wages in their sectors.

The takeaway

We now know what keeps central bankers up at night. Balancing inflation, particularly wage inflation in the face of activity driven by other actors.

Unfortunately, they can’t wait until those lagging effects pass through the system. Markets expect them to act faster, buying and selling bonds that impact the cost of borrowing and currency values.

So the messaging from Jackson Hole was of remain vigilant and keep rates elevated for longer.

“Although inflation has moved down from its peak—a welcome development—it remains too high. We are prepared to raise rates further if appropriate, and intend to hold policy at a restrictive level until we are confident that inflation is moving sustainably down toward our objective,” Jerome Powell said.

“In this era of uncertainty, it is even more important that central banks provide a nominal anchor for the economy and ensure price stability,” Lagarde said. “This means, for the ECB, setting interest rates at sufficiently restrictive levels for as long as necessary to return of inflation to our 2% medium-term target,” said Lagarde.

“Monetary policy may well have to remain in restrictive territory for some time yet,” Broadbent warned.

Japan’s governor advised in the opposite direction. “We think that underlying inflation is still below our target of 2%. This is why we are sticking with our current monetary easing framework,” Ueda advised.

For currencies, that means the US dollar will continue to be strong, Europe and UK will likely drift against the dollar’s strength and the Yen’s weakness is entrenched without intervention.

References

- https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-08-04/us-adds-187-000-jobs-unemployment-rate-drops-to-3-5

- https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/speech/2023/august/ben-broadbent-panellist-at-2023-economic-policy-symposium-jackson-hole-wyoming

- https://www.bea.gov/news/2023/gross-domestic-product-second-quarter-2023-advance-estimate

- https://www.bea.gov/news/2023/gross-domestic-product-second-quarter-2023-advance-estimate