Why traders trust stability over spectacle.

By the OFX team | 10 December 2025 | 5 minute read

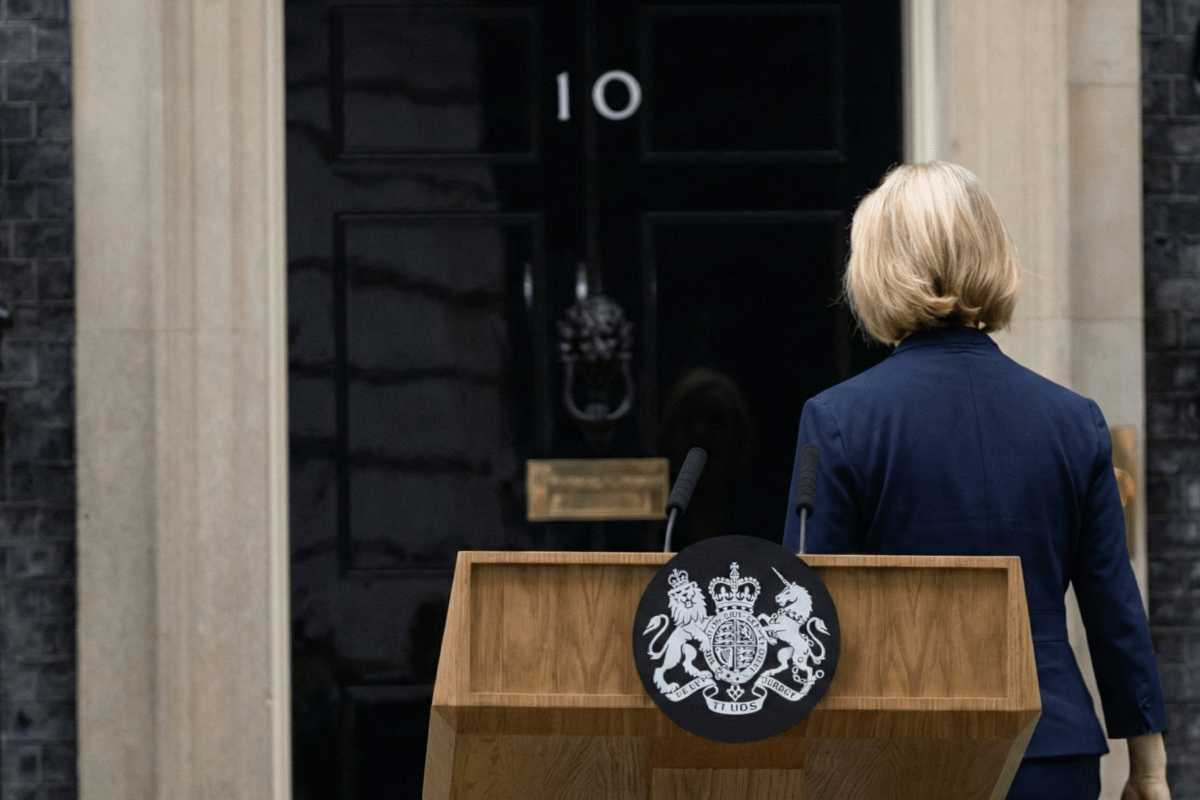

There’s no question that the political calendar in any country can cause turmoil in the currency markets. Who remembers the Liz Truss Mini-Budget in the United Kingdom, in 2022? But while Westminster relishes drama, global investors and currency traders respond only to policy moves with real economic consequences.

A mini-budget that moved global markets.

The Liz Truss Mini-Budget of 2022 remains one of the most striking examples of local politics triggering global market reactions. Conservative MP Liz Truss’ tenure as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom began on 6 September 2022 when she accepted an invitation from Queen Elizabeth II to form a government, succeeding the ousted Boris Johnson; and ended 49 days later, on 25 October, when she resigned her commission.

In that time, the unfortunate Truss and her Chancellor of the Exchequer, Kwasi Karteng, presided over a government that saw the British 10-year gilt (bond) yield rise from 3.03% to a 14-year high of 4.5% in just one week, after her government released a mini-Budget that contained the UK’s biggest tax cuts since 1972 – £45 billion ($90 billion) worth of cuts that were considered unfunded by the markets, funded mostly as they were by more borrowing, and attempts to argue that an economic boom would result, and bring larger tax receipts.

The pound plunged almost 5% against the US dollar, and 7% in two sessions, to US$1.0327, its lowest exchange rate since Britain went decimal in 1971.1

Over four days, long-dated UK government bond yields – which move inversely to prices – rose by more than the annual increase in 23 of the past 27 years. At the height of the Truss mini-Budget crisis, 30-year UK government bond yields – which had started the year at 1%, coming out of COVID lows that had resulted from investors piling into government bonds during the pandemic on ‘safe-haven’ buying assets – reached 5%.

Quite simply, the markets rebelled. It was almost a ‘Lehman moment.’2 Suddenly, investors were worried about the UK’s very fiscal stability.

The spiking bond yields forced many pension funds using Liability-Driven Investment (LDI) strategies to sell their assets to meet margin calls, intensifying the market turmoil. Many UK defined benefit (DB) pension funds, which invest heavily in government bonds, used the LDI strategies – mainly derivative contracts – to help their asset holdings generate enough money to match their liabilities in the form of payouts to pensioners; these funds were forced to sell their assets, including gilts, which only worsened the bond market’s sell-off and lifted bond yields even higher.3

The Bank of England intervened with a promise to buy up to £65 billion ($130 billion) of government bonds, to save funds responsible for managing money on behalf of UK pensioners from collapse.4

Truss’ tax-cutting plan spooked economists, who warned it would undermine the Bank of England’s efforts to tame inflation and force it to raise interest rates even higher.

While fiscal policy rapidly turned expansionary under Truss, the Bank of England was in contractionary mode – meaning that fiscal policy and monetary policy were at counter-purposes. Something had to give. It was the Chancellor the Exchequer, the Prime Minister and the government’s policy package. The markets’ ferocious reaction caused a wholesale government policy U-turn, and Truss sacked her Chancellor, Kwasi Karteng.5 His replacement, Jeremy Hunt, reversed nearly all of the government’s planned tax cuts. Soon after, Truss herself was gone, and the brief, convulsive experiment was over. The pound climbed back to trade above $1.125 last as markets learned of Truss’ resignation.

Lessons traders took from 2022

It had been a brutal experience for currency traders, who had needed all of their experience to work their stops and stay on top of a gyrating trade.

Ever since, players in the pound market have been wary of the political theatre that can affect the market.

Some thought they could have been in for a re-run when the current Labor government delivered its Autumn Budget in November.

Superficially, Labor Chancellor Rachel Reeves faces higher long-dated bond yields than Liz Truss’ government did. In September, the yield on the UK’s 30-year bond hit its highest level since 1998, at 5.75%. Why didn’t that cause the panic that 5% yields caused in 2022? Probably the fact that the rise has not come as quickly – or from as low a starting point – as it did back then.

Laith Khalaf, head of investment analysis at British investment firm AJ Bell, points out that the 30-year gilt yield started 2025 at 4.5% – the rise of about 1.2% over the course of a year to reach 5.7% has allowed investors to absorb and adjust to the rise in yields, which are also offset by income payments from the bonds. A more orderly market, he says, even a declining one, also allows leveraged investors (such as LDI funds in 2022) to post collateral to maintain their positions.6

Political disruption vs market reaction in 2025.

In the political sphere, the 2025 UK Autumn Budget caused chaos. Much of the Budget had been leaked in the preceding weeks, and then on the day, Britain’s fiscal watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), published details of the Budget about an hour before the Chancellor’s speech, sparking a disbelieving frenzy on trading-room floors.7

The Budget leak set the House of Commons ablaze, giving the Conservative opposition plenty of ammunition in terms of the government’s higher spending – in particular, the plan to raise £26 billion ($52 billion) in new taxes to support welfare programs, lifting the tax burden to its highest level since World War Two – and that theatre continues unabated, with the opposition in full voice and the government looking on the defensive. But even with the early look at the detail, for traders, the Budget ended up being ho-hum – certainly in comparison to the impact of the infamous Truss/Kwarteng mini-Budget three years ago.

The Autumn Budget arrived against a bleak backdrop, of sluggish UK economic growth, high debt, weak productivity and political instability8. The GBPUSD pair (known as Cable) had weakened notably in the lead-up to the budget, touching a seven-month low, while against the euro, the pound reached its lowest levels in two-and a-half years. So, there was scope for a relief rally in sterling as the uncertainty came to an end, with the release of the Budget.

Sterling movements following the budget

As it happened, the pound gained about 1% over the Budget week, its strongest rise since early August;9 part of that rise likely came from traders unwinding hedges implemented before the announcement. But looking ahead, many traders believe the pound faces limited upside, as more rate cuts from the Bank of England loom. The central bank kept rates unchanged in November, but easing inflation has strengthened expectations of a cut next month.

Ultimately, as with most currency pairs, it becomes a relative trade based on two sets of interest-rate expectations. The British pound has historically been stronger than the US dollar, maintaining a nominal premium; at US$1.33, it looks substantially stronger than before the British Budget – even though that document showed that the UK has plenty of fiscal problems. A growing anticipation of an interest rate cut by the US Federal Reserve at its December 9–10 meeting is providing a cushion, but markets are also pricing-in a 25-basis points rate cut by the Bank of England (BoE).

References

- https://www.theguardian.com/business/2022/sep/25/city-braces-for-more-volatility-mini-budget-rocks-pound-parity-dollar-bond-tax

- https://www.rostraeconomica.nl/post/breaking-bonds-the-uk-mini-budget-and-the-treasury-turmoil

- https://internationalbanker.com/banking/why-the-bank-of-england-intervened-in-the-uk-bond-market/

- https://internationalbanker.com/banking/why-the-bank-of-england-intervened-in-the-uk-bond-market/

- https://markets.businessinsider.com/news/bonds/uk-news-finance-minister-kwasi-kwarteng-tax-cuts-u-turn-2022-10?utm_medium=ingest&utm_source=markets

- https://www.ajbell.co.uk/group/news/three-years-after-mini-budget-why-isnt-market-panicking-about-higher-gilt-yields

- https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/uks-obr-publishes-economic-outlook-ahead-reeves-budget-speech-2025-11-26/

- https://www.ajbell.co.uk/group/news/three-years-after-mini-budget-why-isnt-market-panicking-about-higher-gilt-yields

- https://www.currenciesdirect.com/en-gb/blog/article/uk-autumn-budget-2025-2026-pound-gbp-forecast

- https://tradingeconomics.com/united-kingdom/currency